By Staff

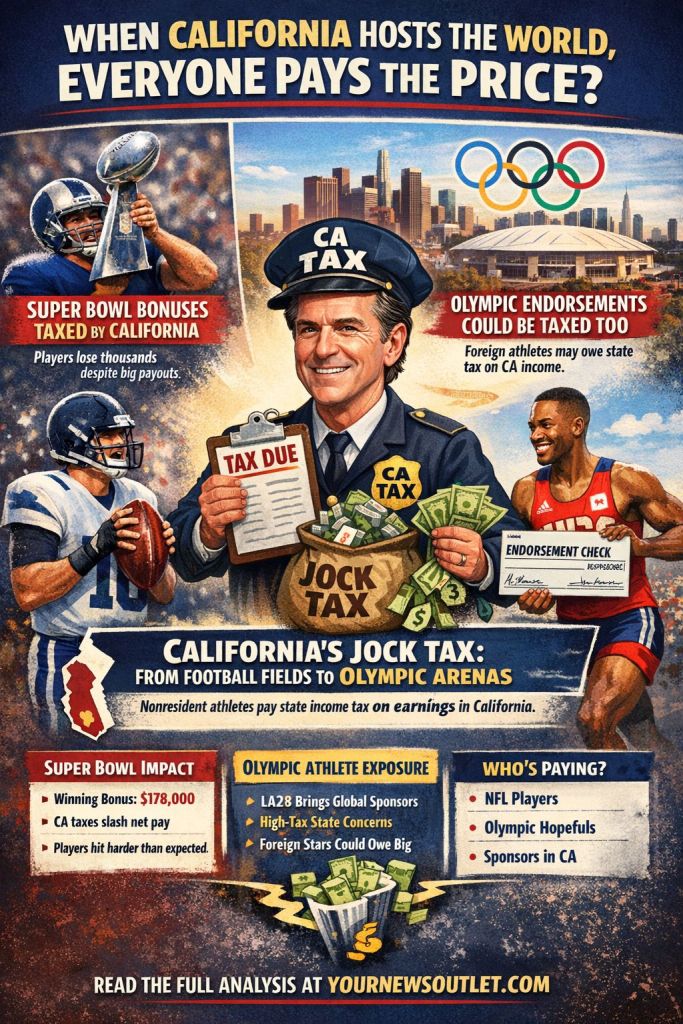

When fans hear the phrase “jock tax,” it often sounds like a special surcharge aimed at wealthy athletes. In reality, it is simply state income tax applied to non-residents who earn money while working in a state. California just enforces that rule more aggressively—and at higher rates—than almost anywhere else in the country.

That reality was put on full display during the most recent Super Bowl played in California. Players on both teams quickly learned that a headline-grabbing bonus does not always translate into headline-grabbing take-home pay. When the game is held in California, Super Bowl bonuses are treated as California-source income, even for players who live and work elsewhere.

California’s reach often goes beyond the single game check. The state commonly uses a “duty-days” formula that allocates income based on the number of workdays an athlete spends in California compared to total workdays during the season. Depending on the circumstances, that formula can pull a portion of an athlete’s entire season salary into California’s tax base. Combined with a top marginal income tax rate of 13.3 percent, the result can be a tax bill totaling tens of thousands of dollars tied to a single appearance.

California’s authority to do this rests on a straightforward principle: income is taxed where services are performed. Residency and citizenship do not matter. Enforcement is handled by the California Franchise Tax Board, and non-resident athletes who earn California-source income are required to file California tax returns. In many cases, taxes are withheld at the source by teams, leagues, or event organizers, meaning the reduction is felt immediately rather than at filing time.

The upcoming 2028 Los Angeles Olympics do not create a new tax, but they dramatically increase exposure. Unlike NFL players, most Olympic athletes are not paid salaries to compete. Their income comes largely from sponsorships, endorsements, media appearances, commercials, and brand activations. When those paid activities take place in California, the income becomes California-source, even if the athlete does not live in the United States and is only in the state temporarily.

This dynamic is especially significant for foreign Olympic athletes. California does not distinguish between American and non-American competitors. The only question that matters is where the paid services occur. If a foreign athlete participates in a sponsor photo shoot in Los Angeles, attends paid brand activations during Olympic week, or fulfills contractual media obligations in California, a portion of that endorsement income becomes subject to California tax.

Most endorsement contracts combine two elements: payment for services and payment for image or likeness rights. California focuses aggressively on the services portion when those services occur in the state. Contracts that fail to clearly separate services from royalties give California greater latitude to argue that a larger share of the deal is taxable. For foreign athletes, the impact can be immediate, as U.S. sponsors or event organizers may be required to withhold California tax upfront, reducing payments long before a tax return is filed.

Despite the increased attention, this is not the result of a new policy. Governor Gavin Newsom has not expanded or created a new jock tax. California’s authority to tax non-resident income earned within its borders predates his administration by decades. What has changed is visibility. High-profile events like the Super Bowl and the Olympics bring global attention to a tax system that has been operating quietly for years.

The Los Angeles Olympics will concentrate global sponsors, international athletes, and nonstop media activity inside one of the highest-tax jurisdictions in the country. For athletes whose Olympic income depends on endorsements rather than salaries, LA28 is not just a sporting event. It is a tax-planning event.

California’s jock tax has already reduced Super Bowl bonuses for NFL players competing in the state. The same rules—applied to endorsements, appearances, and promotional work—are positioned to affect Olympic athletes, including foreign competitors, during the 2028 Games. The Olympics do not provide a tax exemption. They simply shine a brighter light on a system California has enforced for decades, one duty day, one bonus, and one endorsement deal at a time.