By James Williams

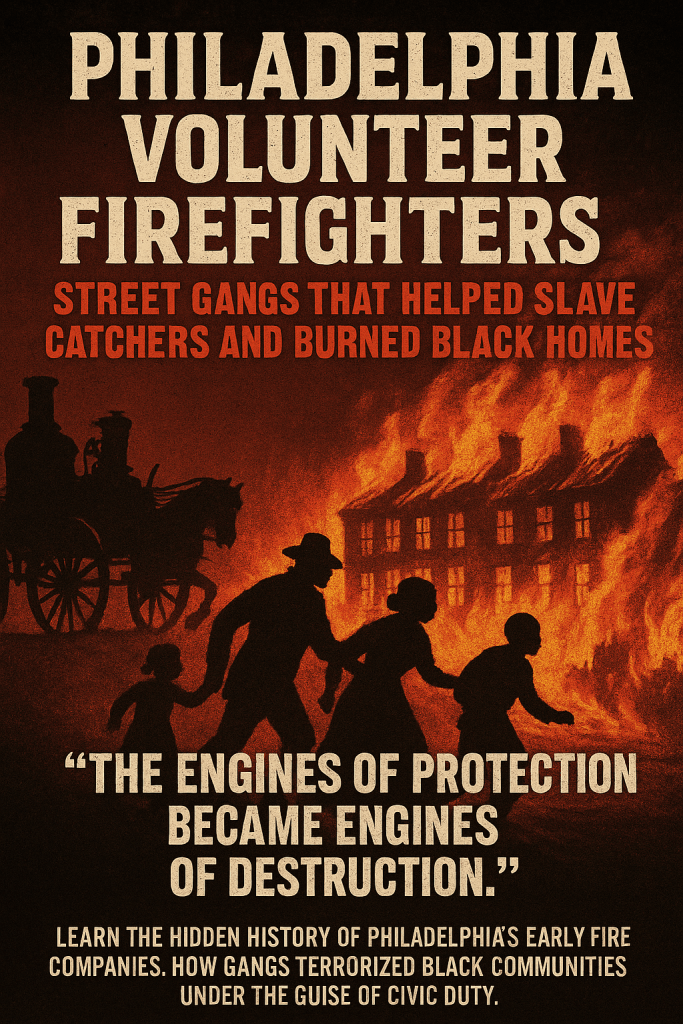

“The engines of protection became engines of destruction… their hands held not the hose but the torch.” — Black Press coverage of the Lombard Street Riot, 1842

I first learned about Philadelphia’s volunteer fire companies back in college. What stuck with me then was the shocking idea that these groups — long celebrated as neighborhood heroes — often acted more like street gangs than civic servants. They brawled in the streets, controlled neighborhoods, and were deeply tied to political machines.

But what I didn’t hear much about at the time was how these same companies, many of them based in independent districts like Northern Liberties, Southwark, Moyamensing, and Kensington, targeted the city’s Black community. These districts were some of the largest cities in America in the early 1800s, and their fire companies became notorious for violence. Their role in racial terror, their support of slave catchers, and their complicity in burning down Black homes and churches rarely made it into the mainstream narrative.

Philadelphia’s early firefighting story is not just about putting out flames — it’s about how power was abused, how institutions turned against the vulnerable, and how Black Philadelphians organized to resist. By revisiting this chapter, we can better understand the roots of civic life in our city and the resilience of those who fought for freedom and dignity.

Fire Companies as Gangs

Volunteer fire companies were neighborhood-based, rowdy crews of young white men. Rivalries were so intense that fires often became battlefields: instead of putting out the blaze, they fought over who would control the hydrant.

The Moyamensing Hose Company and the Southwark “Killers” were especially notorious. By the mid-19th century, these groups acted like gangs, enforcing political influence for Democratic ward bosses and spreading fear through violence.

Independent Districts, Not Just Suburbs

Many of the most violent fire companies operated outside the old core of Philadelphia, in what were then independent districts and townships. Northern Liberties, Southwark, Moyamensing, and Kensington rivaled Philadelphia proper in size and influence, and their firemen served as street enforcers for local politics.

Rivalries between neighborhoods often spilled into open violence, with firemen fighting each other as much as they fought fires. Only after the Act of Consolidation in 1854, when Philadelphia County was merged into a single city, did leaders attempt to bring order. Even then, volunteer fire companies carried on as gangs until the professional fire department was created in 1871.

Turning Against Black Philadelphians

“The fire companies, instead of exerting themselves to arrest the flames or disperse the mob, united with the multitude in destroying our dwellings.” — Petition of Black residents to the Pennsylvania legislature, 1834

Black citizens bore the brunt of this lawlessness. Fire companies were frequently involved in anti-Black riots, including the Lombard Street Riot of 1842, where they helped white mobs attack a peaceful Black parade, burned churches, and destroyed homes.

Eyewitnesses described Southwark firemen storming through the streets in 1842: “The Southwark Hose, with engines and axes, came not to save but to destroy. They bore down upon our people with as much fury as the flames.”

Abolitionist William Still later confirmed the community’s fear, writing that “the colored people knew too well that the firemen, instead of protecting life and property, would themselves join in the outrage.”

Instead of defending residents, the fire companies weaponized their authority against free Black citizens.

Helping Slave Catchers

“Kidnappers prowled about the city like wolves in search of prey. No colored man, woman, or child was safe.” — William Still, The Underground Railroad (1872)

The violence did not end with riots. Volunteer fire companies were also deeply entangled with the world of slave catching and kidnapping. Under the Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850, agents prowled Philadelphia hunting fugitives and even seizing free-born Black residents.

With neighborhood control and political protection, fire companies provided cover, intimidated witnesses, and disrupted abolitionist rescues.

One notorious example was the 1825 kidnapping of Cornelius Sinclair, a free Black boy seized by the Johnson and Kelly gang. Sinclair’s ordeal exposed how gangs worked hand in hand with fire company allies who ensured kidnappers could move unchallenged through the city.

Black Resistance

“The entire colored population is in jeopardy. We live in the midst of thieves, kidnappers, and assassins.” — Robert Purvis, Philadelphia abolitionist, 1830s

Despite the danger, Black Philadelphians organized. Purvis, Still, and others built Vigilance Committees that raised funds for legal defenses, organized watches, and sometimes mounted armed resistance. These committees became the backbone of one of the most effective branches of the Underground Railroad, turning Philadelphia into both a battleground and a beacon of resistance.

The End of the Volunteer Era

“The laws are made for us, but not executed in our favor.” — James Forten, abolitionist leader

By the late 1860s, the violence of the fire companies had become intolerable. Forten’s warning was nowhere clearer than in the way firemen operated. In 1871, reformers created the professional Philadelphia Fire Department, finally ending the volunteer era. But the scars remained, leaving Black communities with a long memory of civic institutions that had turned against them.

Conclusion

Today, when we talk about “gangs” and “thugs” in Philadelphia, it is almost always framed as a modern problem — and almost always a Black one. But the first organized gangs in this city were not Black. They were white volunteer firemen, operating under the banner of civic service while terrorizing neighborhoods, helping slave catchers, and burning down Black homes and churches.

Gang violence in Philadelphia did not begin in Black neighborhoods. It began with institutions that were supposed to serve all citizens.

As an adult, I remain grateful for the lessons I learned as a history major. My professor, Dr. Girard, always insisted on teaching the hard truths about America — not polished myths, but the realities of violence, racism, and resistance that shaped this nation. This history of Philadelphia’s volunteer fire companies is one of those truths. Remembering it matters, because only by seeing the origins of our struggles clearly can we begin to seek real justice.