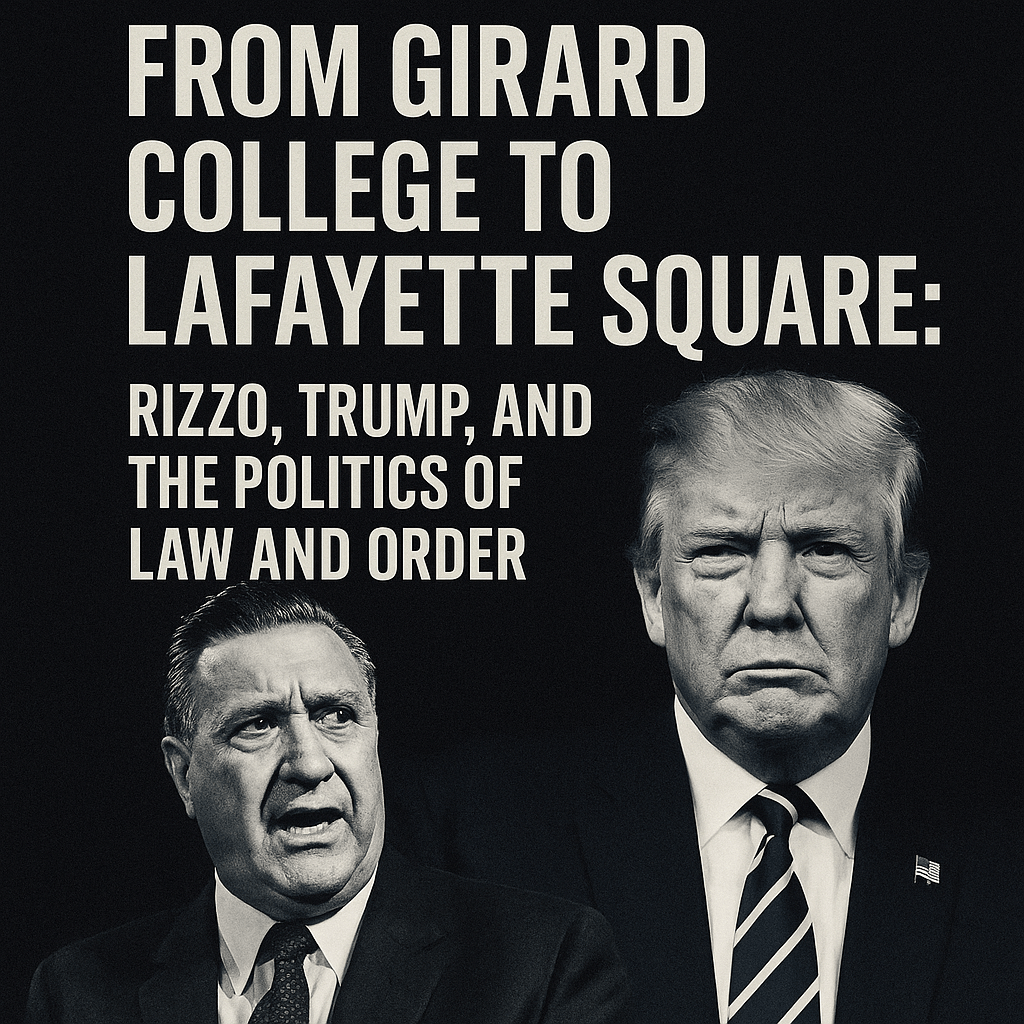

Editor-in-Chief | The Uptown Standard

In the summer of 1967, Philadelphia stood at the intersection of civil rights and state repression.

It began at Girard College, an elite all-white boys’ school fortified by stone walls and exclusionary tradition. Black students, NAACP leaders, and activists gathered at its gates, demanding integration and justice. For seven weeks, they protested peacefully. But Police Commissioner Frank Rizzo wasn’t interested in peace. He was interested in control.

Under his orders, police descended in riot gear, swinging batons at teenagers and clergy alike. Protesters were beaten, arrested, and publicly humiliated. To Black Philadelphians, Rizzo became a symbol of state violence. To conservative white voters, he became a hero—a man who “restored order.”

And Rizzo wasn’t finished.

Just a few months later, on November 17, 1967, Rizzo led another crackdown—this time near South Street, where more than 3,500 mostly Black high school students gathered outside a school board meeting. They called for curriculum reform, cultural inclusion, and a voice in how their schools were run.

Rizzo’s response? Over 100 riot officers, indiscriminate force, and mass arrests. More than 50 were jailed, over 20 hospitalized, and at least one priest was clubbed in the chaos. Rizzo called it “necessary.” Civil rights advocates called it a “brutal suppression of youth voices.”

I believe Rizzo would have loved to parade the entire Philadelphia police force down South Broad Street in full formation. That was his language—spectacle and suppression.

And now, in 2025, President Donald J. Trump—currently in his second term—is speaking that same language.

Just this morning, Trump finally got his long-desired military parade, an idea he floated back in 2017 after attending France’s Bastille Day celebration. Today’s spectacle marked the Army’s 250th anniversary: over 6,000 soldiers and 128 Army tanks rolled through Washington, D.C. It was less celebration, more projection—a flex of American power aimed at a restless, divided nation.

But it didn’t come in a vacuum. In recent weeks, protesters across the country have once again filled the streets—marching for racial justice, fair immigration policy, and economic reform. Their reward? National Guard deployments, federal agents in tactical gear, and “zero tolerance” crackdowns. Peaceful protests met with military-style policing—just like Philly in ’67.

From Girard College, to South Street, to Lafayette Square, to today’s Pennsylvania Avenue, the same playbook keeps showing up: define protest as chaos, define order as force, and use the badge—or the boot—as a political brand.

Rizzo built his legacy on that. Trump has doubled down on it.

And though the Rizzo statue may have come down in 2020, its shadow lingers—marching beside tanks and saluting a flag that too often waves for power, not for people.

The question that faced us in North Philly 58 years ago still faces us now:

Is law and order about protecting citizens—or silencing them?